Lima, junio de 2023, 7(1), pp. 126-140

De musica latine scribenda: How to approach a Latin text as a composer without summoning a demon in the process

De musica latine scribenda: Cómo acercarse a un texto escritoen latín como compositor sin invocar a un demonio en el proceso

Juan Carlos Aliaga del Bosque ↓

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú

![]() https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3058-0971

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3058-0971

DOI

Abstract

While composing vocal music, it is usually required an extra “set of rules” that is generally related with the language of the text used in the music. Each language has characteristics connected with its pronunciation, prosody, meaning, etc., that are necessary in order to set the text in a way that is understandable, but also some of these “quirks” can be exploitable and shape the music in a way that is closer to the sound, rhythm or even the culture carried by the language. This first paper on the topic addresses the use of Latin language in musical composition, as many others have tackled its pronunciation in performance but there is not much written about how a composer can use the language with confidence and efficiency. In this paper, the concepts of syllable length and tonic accent in Latin will be introduced and they will be explained and applied through musical examples from different historical periods.

Keywords

Music written in latin, vocal music, classical latin, latin prosody, vocal music composition

Resumen

Al escribir música vocal, usualmente, es necesario tener un “conjunto de reglas” suplementario, el cual está, por lo general, relacionado al idioma del texto usado en la música. Cada lengua tiene características conectadas a su pronunciación, prosodia, significado, etcétera, las cuales son necesarias para que el texto empleado sea inteligible, pero algunas de estas peculiaridades también pueden ser explotadas y así dar forma a la música de una manera en la cual ésta puede ser más cercana al sonido, ritmo o incluso la cultura llevada por el idioma. Este primer artículo aborda el uso del latín en la composición musical, ya que muchos tratan sobre su pronunciación en la interpretación, pero no hay mucho escrito sobre cómo un compositor puede usar el idioma con confianza y eficiencia. En este artículo, los conceptos de longitud silábica y acento tónico son presentados, explicados y aplicados a través de ejemplos musicales de distintos periodos.

Palabras clave

Música escrita en latín, música vocal, latín clásico, prosodia latina, composición de música vocal

Recibido: 15 de marzo de 2023 / Aceptado: 29 de marzo de 2023

Introduction

A considerable amount of the vocal music repertoire are settings of Latin texts, especially writings of religious subjects. This fact, like in other languages, has inspired literature oriented towards helping singers with the right pronunciation of Latin. On the contrary, not much has been written in order to help composers in the duty of setting texts created in this language in a way that these are not only vehicles for independent sounds that will have a pitch assigned, but also for meaning and tradition, like a native speaker would do with its own language.

It is true that currently Latin is not the official language of any country except for Vatican City, does not have a society of native speakers and that the presence of classical languages in schools’ curricula have decreased through time (Encyclopedia, 2022). Nevertheless, we know it very well through the copious amount of literature written in it and we also possess information about how it sounded and how it has changed. We might not know completely how a Roman would have sounded while reciting verses from Virgil’s Aeneid, but we have reconstructions used by plenty of people who study Latin and speak it proficiently as non-native speakers. These two facts imply two main contrasting issues: The former has brought us to a moment in time in which the audience is not familiar with the language and there is no real necessity for it to be understandable. Whereas the latter means that we do have enough information to keep the message intelligible and could use this as an advantage for our music: Every language has its own quirks and because of these we do not go to the opera to listen to a Spanish translation of Ades’ The Exterminating Angel or an English one of Torrejon y Velasco’s La Purpura de la Rosa. We could take care of the way we use Latin the same way we do with any currently spoken language. For this first article on the topic, I will focus on Classical Latin grammar and prosody, as most of the elementary courses and information corresponds to the standardization of the Latin of this period as the one taught in schools.

As composers we cannot directly work on pronunciation besides loosely indicating it (e.g., Classical or ecclesiastical pronunciation) or specifying each phoneme, but in the end, it will rely on the performer.

There are two main concepts I want to address that the composer can use and write precisely in the score. These are vowel length and stress.

Part I: Definitions

Vowel and syllable length

In some languages, like Finnish, Japanese, and others, there is another factor that determines meaning besides the phonemic part of the message: The duration of the sounds also must be taken in count to understand a word. Both languages mentioned before may use double letters in order to differentiate between a long and short sound. A syllable containing a long vowel, or a vowel followed by two consonants will be long. In some cases, two words may sound identically except for the length of one syllable. Examples of this property are words like:

Finnish: tuli (fire) and tuuli (wind) / valita (to choose) and vallita (to dominate)

Japanese1: kutsu (shoes) and kutsuu (pain) / kado (corner) and kaado (card)

Latin also has long and short vowels and syllables (Gildersleeve, 1903). Long vowels are notated by a line on the letter called macron. A syllable is long by nature when it contains a long vowel or a diphthong (ae, oe, au, ei, eu). It can also be long by position when a short vowel is followed by two or more consonants or a double consonant. Otherwise, the syllable is short. The word ‘Rōmānī’ (Romans) has three long syllables by nature as all its vowels are long. ‘Amnis’ (river) begins with a long syllable by position, as the vowel is followed by two consonants. Words that are written identically may get a different meaning depending on the syllables’ lengths:

Malum (bad) and mālum (apple) / os (bone) and ōs (mouth) / est (he/she/it is) and ēst (he/she/it eats)

As it is written above, it is important to consider vowel length semantically, but it is also a very important part of Classical Latin’s sound. Verse relied strongly on syllable length as we will see later and it was an important part of regular speech. Augustine of Hippo wrote and complained about how some non-native speakers preferred the use of the word ‘ossum’ (Vulgar Latin word for ‘bone’) instead of ‘os’ (Classical Latin word for ‘bone’), as they were not familiar with the use of long or short vowels and would confuse it with ‘ōs’ (mouth) (Adams, 2007, p. 261). More interesting examples of its importance can be seen in a video made by Ranieri in 2019.

Stress accent

Similar to Spanish, words in Latin can be affected by the position of the emphasized syllable:

Spanish: trabajará (you will work) and trabajara (I/he/she/it would work (subjunctive)

Latin: pérvenit (he/she/it arrives) and pervénit (he/she/it arrived)2

The rules to know what syllable should be accented are simple:

- If the word has only one syllable, that one syllable is to be accented.

- If the word has two syllables, it is always accented on the penultimate syllable.

- If the word has three or more syllables, there are two cases:

-

- If the penultimate syllable is long, it is accented on that syllable.

- If the penultimate syllable is short, the antepenultimate syllable is to be accented.

This is commonly known as the “Penultimate stress rule”.3 As shown above, stress accent is important not only to get the right pronunciation of a word, but also the correct meaning. Now we can understand why ‘pervenit’ and ‘pervēnit’ are accented on the antepenult and the penult respectively.

Part II: Musical application and examples

Verse

Let’s look first at texts in verse, as it might be the most complicated case. Verse in different languages have an inner musicality provided by the meter, a particular rhythm given by a combination of words and/or rhyme. In Classical Latin it is unusual to find rhyme, but it has an extensive use of meter. As an example, works like De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things by Lucretius) or Aeneis (The Aeneid by Virgil) are written in a meter called dactylic hexameter. It has a specific combination of long and short syllables with a certain degree of freedom: We need six groups (called feet) where each one is a group of two long syllables (called spondee), or a group conformed by one long syllable and two short ones (called dactyl). It is very common, if not a rule, for the last two to be a dactyl (penultimate) and a spondee (last). This is usually represented as:.

| – u u | – u u | – u u | – u u | – u u | – – |

Where long syllables are ‘–’ and short are ‘u’. Each one of the 4 initial feet (separated by a stroke symbol ‘|’) show these two possible options. We can analyze (usually called ‘scan’) the first line of the Aeneis:

‘Arma virumque canō, Trōiae quī prīmus ab ōrīs’

Scanned:4 ‘Ārma vi | rūmque ca | nō, Trō | i ǣ quī | prīmus ab | ōrīs’

| - u u | - u u | - - | - - | - u u | - - |

Whole works are written with a meter and this internal rhythm is an important part of the musicality of the Latin verse. Our aim now is to show different approaches in which we can represent it in our settings.

An example of a great musical environment for verse and meter to be clear is the work done by Eusebius Toth and Tyrtarion, a choir part of the Accademia Vivarium Novum, one of the most important classical language schools. They set poems to music that represents the meter and rhythm in which the verses were written. The rhythm is precise: quarter notes for long syllables and eight notes for short ones (we might find longer rhythms in the end phrases). Let’s see an example:

‘Vīvāmus, mea Lesbia, atque amēmus’

This is the first line of Catullus’ “Ad Lesbiam”, a very well-known poem. It is written in a particular meter called Phalaecian Hendecasyllable, which has this syllable structure: × × – u u – u – u – –; where x can be short or long, - is long and u is short. This is how the members of Tyrtarion represented the meter in their setting.

Figure 1

Tyrtarion’s example

Nota. Toth (n.d.).

The texture is homophonic and there is no time signature nor regular barlines, as the latter only separate each line of the verse. As we can see, there is a direct correlation between the length of the syllable and its duration in the piece. The rhythm is dictated by the meter of the poem itself. We can find interesting combinations, especially syncopations and one might find different initial options. Tyrtarion has made plenty of these adaptations and their rhythms vary depending on the meter used by the writer.

A contrasting example is an extract from a work composed by Carl Orff called Catulli Carmina (1943), where on the same text the meter has been blurred by using similar rhythms in almost the whole passage:

Figure 2

Orff’s example from the second part of Act 1 of Catulli Carmina

Nota. Orff (1943).

The only exceptions are the half-note in ‘vīvāmus’, what is an agogic accent on the correct syllable and ‘amēmus’, where we have a good representation of the last two syllables of this type of meter (both long). The method used by Tyrtarion has been also employed in the past by other composers like Franchino Gaffurio, b. 1451, who in his De Harmonia Musicorum Instrumentorum Opus (1518) wrote music for a text composed by Lancino Curzio. Here we present the first stanza:

‘Mūsicēs septemque modōs Planēte

Corrigunt septem totidemque chordīs

Thrācis antīquī lyra personābāt

Cognita syluīs.’

Figure 3

Musical extract from Gaffurio’s De Harmonia Musicorum Instrumentorum Opus

Nota. Gaffurio (1518).

We can see a very similar process where breves are assigned to long syllables and semibreves to short syllables. The composer even writes explicitly about employing this method (Gaffurio, 1518). It is important to mention that he was taught Latin, and his treatises are all written in this language.

It is common to find that the stressed syllable is long, but it may also be short (like the case of the word ‘modōs’) and therefore this combination might hinder the perception of the actual stress of the word in the music (by the effect of an agogic accent). Thus, this procedure prioritizes the rhythm generated by the meter through the syllable’s length instead of the stress accent of words.

This practice permits a good intelligibility of both the lyrics and the musicality of the poem, emphasizing its meter. For composers, this method might be constraining. We can find examples of freer treatment of the verse. Next, we have a setting of a section of the Aeneid’s fourth book by Jacob Arcadelt (1956).

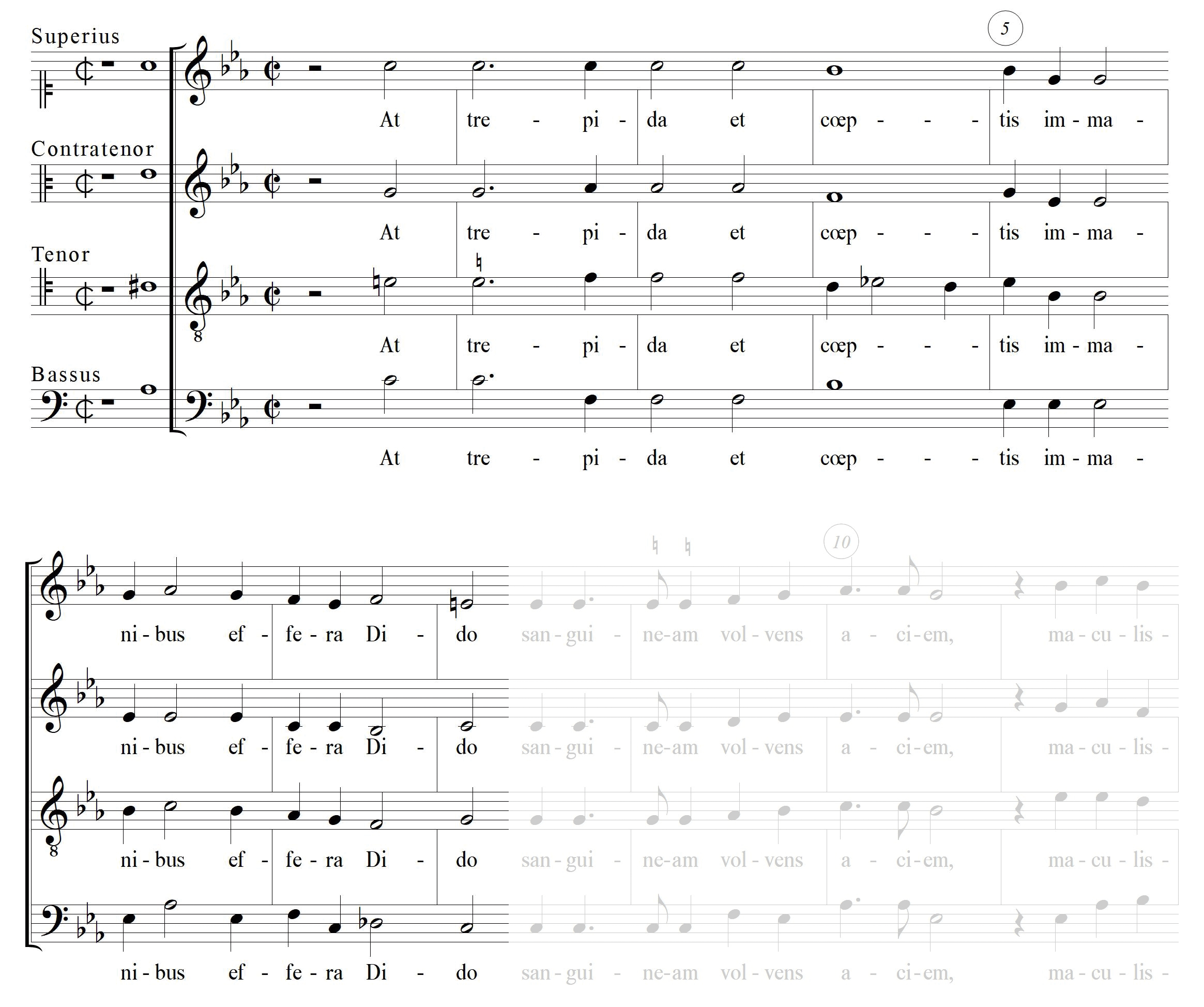

‘At trepida et coeptīs immānibus effera Dīdō

sanguineam volvēns aciem, maculīsque trementīs

interfūsa genās et pallida morte fūtūrā’.

Figure 4

Arcadelt’s At trepida (mm. 1-8)

Nota. Arcadelt (1956).

In this example the stressed syllables are the ones who get longer figures to represent them by an agogic accent, but we also see in the word ‘effera’ that the stressed is generated by a tone accent (the highest note is given to the stressed syllable). These are two different ways in which we can get the stress on the right syllable that applies to any language with this characteristic use of tonic accents. Similar to our previous case, by using duration in order to emphasize, we have lost some of the natural rhythm of the meter (some words like ‘immānibus’ and ‘Dīdō’ still have some relation to its syllables’ length). Nevertheless, the next line finds a middle point by assigning different durations per word that keeps length and stress distinguishable.

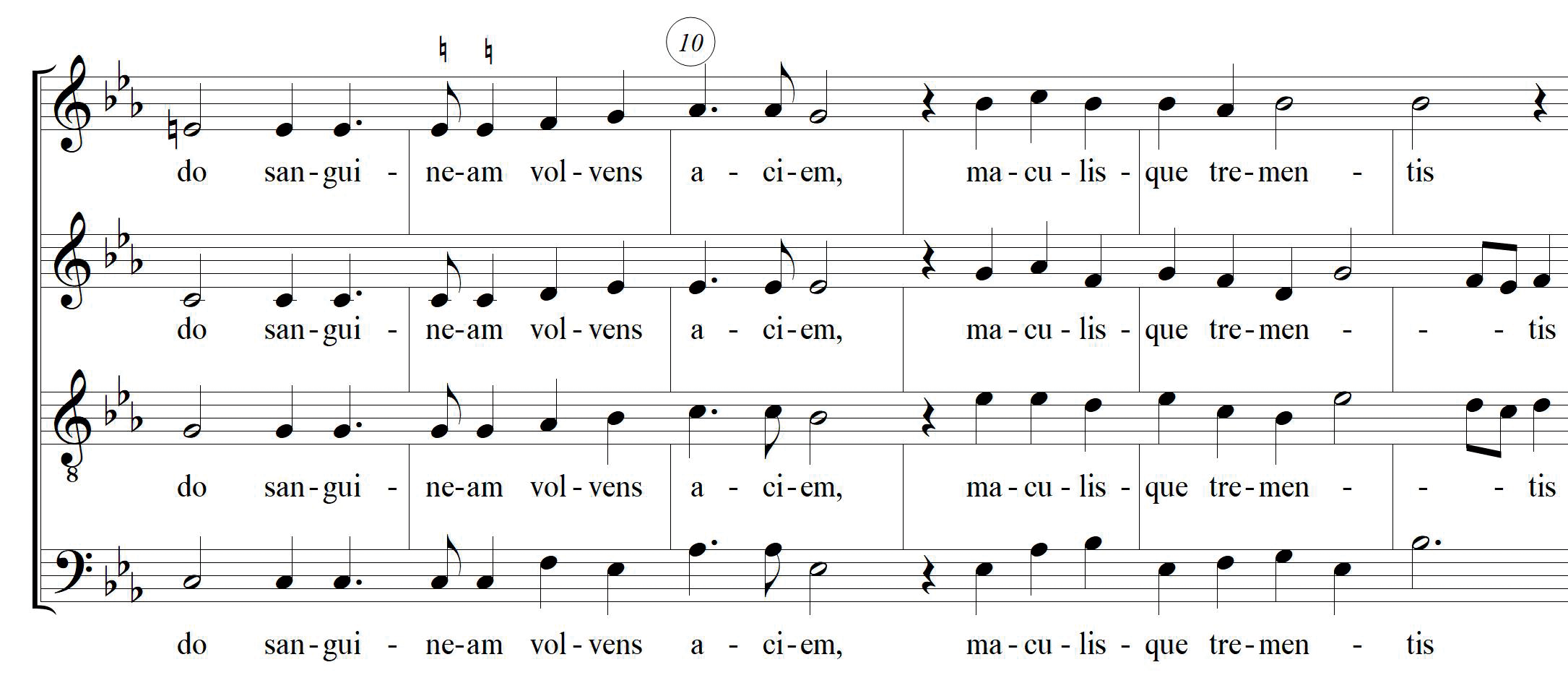

Figure 5

Arcadelt’s At trepida (mm. 8-13)

Nota. Arcadelt (1956).

Let’s look at the word ‘sanguineam’. The accent is on the antepenultimate syllable, which gets the longest duration. The only short syllable is the penultimate and gets the shortest duration. Long syllables get a shorter duration than the accented one, but longer than the short one. ‘Volvēns’ has two long syllables with the same duration. ‘Aciem’ might be a particular case as it is before the comma, but still has a long duration for the accented short syllable, a shorter duration for the short one and a longer duration for the last long syllable. ‘Maculīsque’ is represented with the same rhythm for all syllables regardless of the fact of having a long penultimate syllable, but this might be connected to a musical reason as we are close to the end of the phrase and longer rhythms would have slowed down the flow of the music to the end of the phrase. ‘Trementīs’ has a long and stressed penultimate syllable, what works well as the composer is able to ornament it just to end the phrase with the last long syllable.

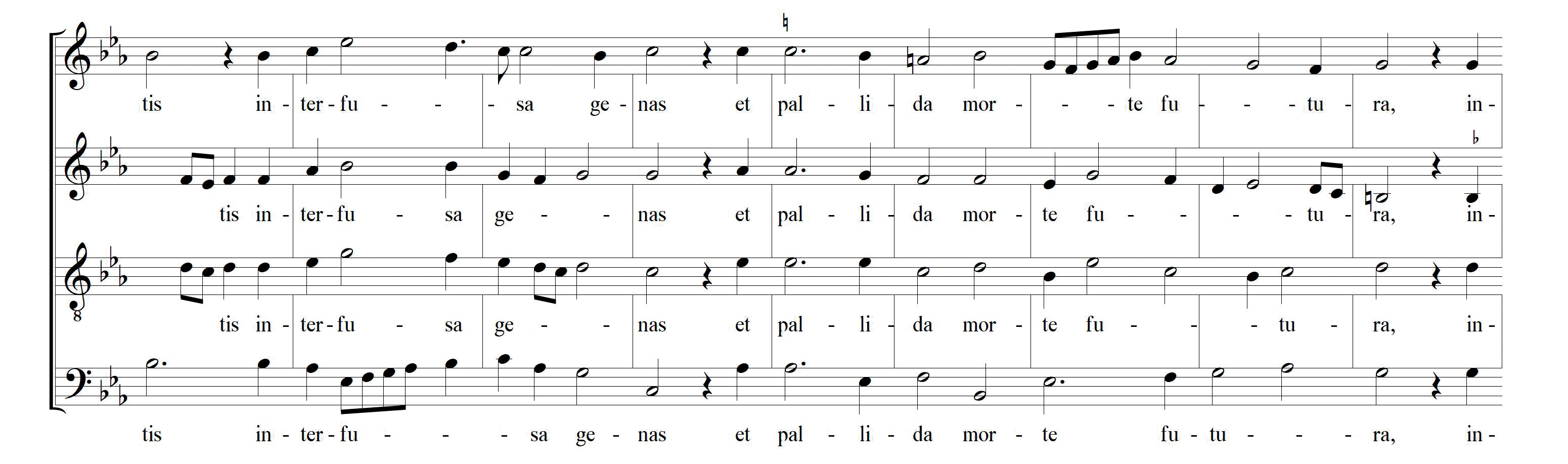

Figure 6

Arcadelt’s At trepida (mm. 13-21)

Nota. Arcadelt (1956).

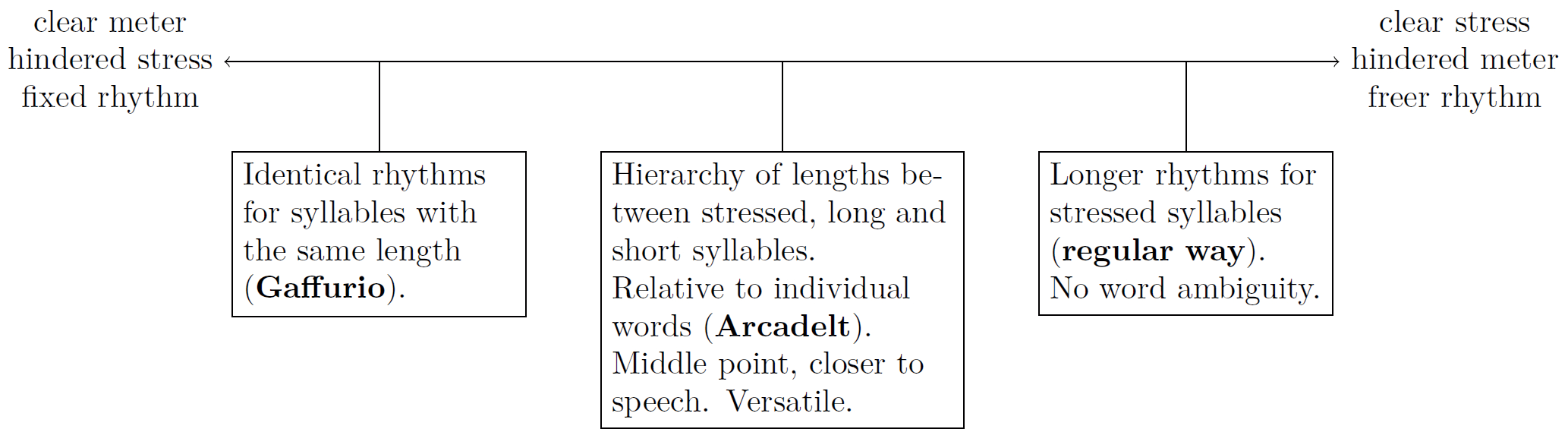

The last line shows similar solutions along the whole excerpt, but a very interesting one is the word ‘fūtūrā’. We find three long syllables that gives enough space to the composer to develop the ending of the section with a two-step cadence. To summarize what has been exposed, we can make a diagram.5

Figure 7

Different approaches to Latin prosody in text-setting as a spectrum

We can move along these 3 states depending on the sound we are looking for. From a traditional way of reading poetry to how we usually work with other languages with stress accent and no syllable length. I consider that the middle point is a state that has not been explored enough and could be a standard way of treating Latin in verse. The idea of having hierarchies in individual words not only permits variety as different words can have different rhythms that keep the length grading, but admits systematic processes that composers can use to generate rhythmic material as well.

Prose

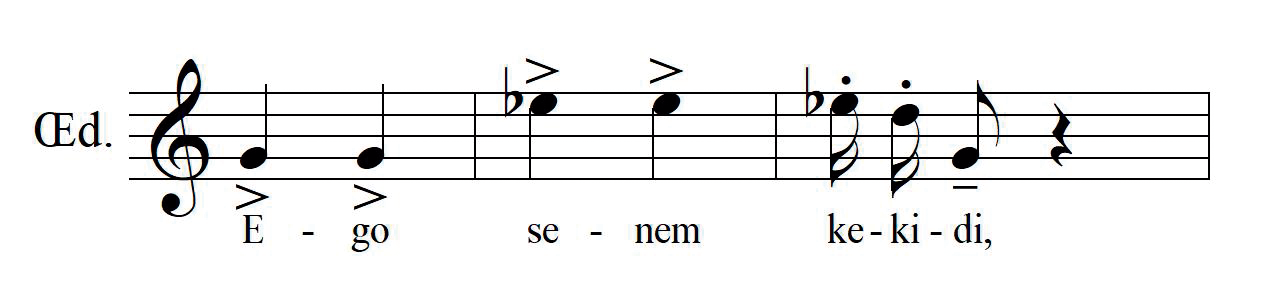

>When working with prose, technically we do not have restrictions. But as it was mentioned before, stress accent is important in order to avoid ambiguity and there is evidence of vowel length in regular speech. For that reason, the “middle point” approach mentioned before would be a good practice and would avoid doubts in words that sound identical except for its stress and length. A good example of this issue is in Oedipus Rex, an opera-oratorio written by Igor Stravinsky (1927). The phrase we are looking at is ‘Egō senem cecīdī’6 (I killed the old man). In the music, the word ‘cecīdī’ (accented cecídi) has its first syllable accented by the strong beat of the measure, what sounds ‘cecidī’ (cécidi). By this displacement of the stress the word changed its meaning from ‘I killed’ to ‘I fell’, making it a nonsensical phrase.

Figure 8

Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex

Nota. Stravinsky (1927).

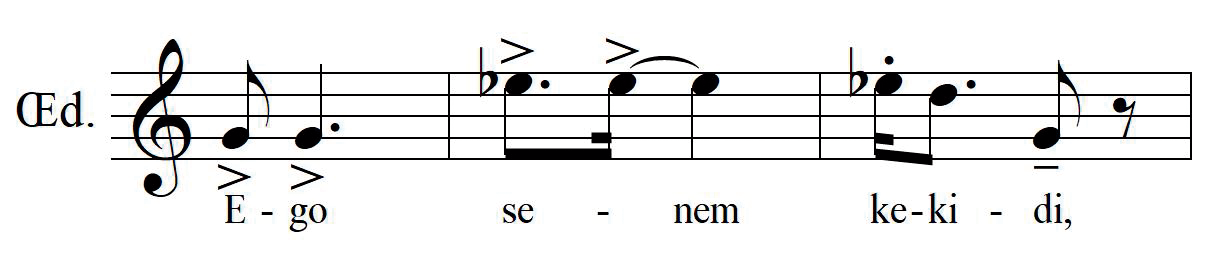

Stravinsky was aware of this problem and mentioned it in his Memories (1960). He even comments about how it was attempted to fix it in performance (probably by accenting the second syllable), but “remains awkward” (Stravinsky, 1960). The hierarchical approach could have been useful, as employing figures like the ones in Figure 9 would have kept the stress and length closer to the right syllable, avoiding the problem.

Figure 9

Possible solution to Stravinski’s example

Another issue may arise while working with words that are indistinguishable except for the length of a syllable. Some examples are the settings made by Johann Hasse, Gregorio Allegri and Bernardo Alcedo of the Psalm 51 (Miserere). In the text we can find the next sentence:

‘Tibi sōlī peccāvī, et malum cōram tē fēcī’

“I sinned against you only, and I did evil to you in your presence”

Here the word ‘malum’ (bad, evil, bad thing) could be misunderstood as ambiguity might arise given that ‘mālum’ (apple) is similar.

Figure 10

Hasse’s Miserere

Figure 11

Alcedo’s Miserere

Nota. Alcedo (1848).

Figure 12

Allegri’s Miserere

In order to avoid confusion, we should have a longer last syllable or similar lengths in ‘malum’ (the first syllable could be similar in case we want an agogic accent on the stressed syllable). The main difference among these three examples is the relative length of the syllables. In Hasse’s example the first syllable is extended and ornamented for a long period of time. In Alcedo’s example the length given to the first syllable is longer in comparison to the second one, but the proportion is not as problematic as in Hasse’s example. Allegri kept both rhythms equal, closer to what we expected. The first example may look like an intentional lengthening of the word to make obvious the first long syllable and it would not be representing the actual sound of the word, besides being the ‘mālummalum’ dichotomy one of the best-known examples in Latin of a homograph, it might catch a Latin-speaker’s attention. It is true that the context will in various cases solve any ambiguity, but this is even an issue during regular speech, as mentioned in the first part. It is also important to mention that other languages, like Japanese, do include this factor in their music as shown in Nakata (2005).

Part III. Conclusions

Here I have worked around with one variable, which is rhythm. We can do many things with it, but in combination with other ways to show stress accent (like the natural strong beat of a time signature, written accents, tone accents, orchestration, etc.), we can get such freedom and only rely on rhythm to show syllable length.

Later in history, Latin lost its syllable length and relied mostly on stress accent. A well-known example is the Carmina Burana (The one used by Carl Orff in a work with the same name). The rhythm in these poems is given by the stress of syllables. It could be covered in a next article.

Having a Latin-speaker in our audience or reading our scores is unlikely to happen, but what I propose is that this issue should not be our main focus. Writing music with a text in, for example, English or French for someone who does not speak any of those languages will require certain research as they can be phonetically inconsistent. It is almost mandatory to learn the basics inorder to use the text correctly as we want to do the best we can with it and this happens with any language. We are all non-natives speakers or we do not know anything about Latin, therefore learning about its peculiarities should also be important not only to get the meaning right in our music, but also to get closer to what that language is. If we do this right, we might get Latin to the position it should have had: Another language with its own sound, as our own.

Referencias

Adams, J. N. (2007). The Regional Diversification of Latin 200 BC to AD 600. Cambridge University Press.

Alcedo, J. B. (1848) Christus factus y Miserere [Sheet music].

Arcadelt, J. (1956). At trepida [Sheet music]. In O. Helmuth (Ed.), 5 Motets on texts by Virgil. Das Chorwerk.

Encyclopedia. (November 29, 2022). Latin in Schools, Teaching of. https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-andmaps/latin-schools-teaching)

English, M. C. & Irby, G. L. (2015). A New Latin primer. Oxford University Press.

Gaffurio, F. (1518). De harmonia musicorum instrumentorum opus, liber quartus et ultimus. (Reprinted New York: Broude Bros., [1979]; Bologna: Forni, 1972).

Gildersleeve, B. L. (1903). Latin Grammar. Macmillan.

Nakata, H. (2005). The relationship between note values and speech timing – Moraic representation in Japanese children's songs. Reading, 8, 69-93. https://www.reading.ac.uk/internal/appling/wp8/Nakata.pdf

Orff, C. (1943). Catulli Carmina. Ludi scaenici - Szenische Spiele “Rumoresque senum severiorum omnes unius aestimemus assis” [Musical score]. Schott Music.

Stravinsky, I. (1927). Oedipus Rex. (Republished by Boosey and Hawkes, 1927).

Stravinsky, I. & Craft, R. (1960). Memories and commentaries 1882-1971. Garden City.

Toth, E. (n.d.). 5 - Vivamus. Tyrtarion. https://tyrtarion.net/catullus/005-vivamus